Indigenous knowledge, histories and futures are woven throughout PST Art projects at UCLA and beyond

As Native American Heritage Month draws to a close, and as many of us prepare to gather with family and friends in gratitude, there are also opportunities to spend time with the indigenous perspectives that are threaded throughout PST Art 2024: Art & Science Collide, both here at UCLA and by virtue of our alumni representation across the regional art event, the largest in the nation.

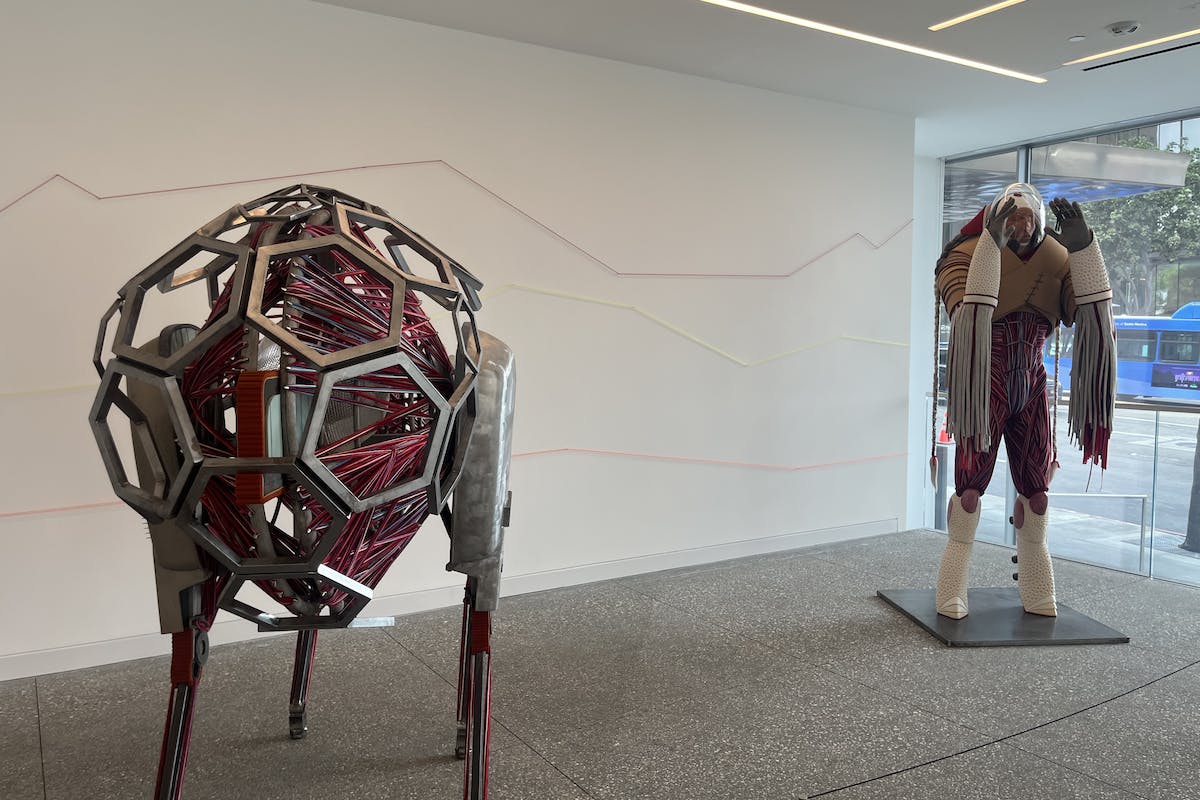

Standing sentry in the lobby of the Hammer Museum at UCLA a are a series of enigmatic inter-dimensional travelers traversing the space-time continuum, a commissioned work titled Sovereign (2024), by Cannupa Hanska Luger. Born on the Standing Rock Reservation in North Dakota, Luger is an enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold and is Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara and Lakota. This intricate large-scale work is part of the Hammer’s PST Art exhibition Breath(e): Toward Climate and Social Justice.

Image: Sovereign (2024), by Cannupa Hanska Luger in the Hammer Museum Lobby / credit Jessica Wolf

Luger’s work is also reflected in two other PST Art projects, and he has served as one of the lead artist ambassadors for this year’s third iteration of the Getty’s ambitious art event. All three of his PST Art projects are embedded in a holistic theme, which Luger calls “future ancestral technologies.”

“As an Indigenous person, I'm always trapped in this idea that our history, our cosmology, all of this is trapped in the past,” he said at an opening press event for PST Art. “And simultaneously, I'm watching green economies develop at present that seem to be co-opting Indigenous knowledge. And I'm like, can we acknowledge where that technology comes from? And then you'll have 10,000 years of proof of concept versus five years playing the game with investors.”

Future ancestral technology is an exploration into time and space and how we can navigate through both of those things, Luger said.

Image: Sovereign (2024), by Cannupa Hanska Luger in the Hammer Museum Lobby / credit Jessica Wolf

“Institutions, museums can hold our memory and our history like time capsules,” he said. “And so, as artists, as scientists, as people presently developing culture, we are actually making those time machines that we dream of, and they're just navigating through a fourth dimensional space that we can't quite yet comprehend.”

On Friday November 22, the UCLA Film & Television Archive invited acclaimed Canadian filmmaker Danis Goulet (Cree/Metis) for a screening of her dystopian film Night Raiders, which is set in a post-Civil War North America in the year 2024. The film follows Niska (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers), a Cree woman who joins a resistance movement against the oppressive military government in order to save her daughter. The evening was part of the Archive's PST Art screening series Science Fiction Against the Margins.

In a post-screening Q&A, Goulet talked about her inspiration for the film, which was in part informed by the history of Canada’s residential school system and the harm it caused indigenous communities. All of her work deals with the impact of colonization and the impact it continues to have on indigenous people and families. She also drew on Cree language and traditions for her film, traditions that respect rocks and minerals as living things—and thereby her Cree characters treat machines as living things, given that they are made of minerals.

Image: UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television professor Kathleen McHugh and filmmaker Danis Goulet / credit Robert Macaisa

Goulet sees an emergence of attention toward indigenous futurism, in keeping with interest in Afrofuturism.

“I don't know that much about futurism as a theory,” she said. “It’s more so that we as indigenous people were not meant to exist in the future. We never show up in futuristic spaces or in sci-fi spaces and for us to declare that we have a future is a subversive act. And then to place us into the actual future, even if it's imagined and even if the future isn't any better, maybe even be worse in a post-Civil War in North America, that we are still here. And that saying that it's almost like a declaration of, we have always been here, we are still here and we will always be here.”

Image: (L-R) UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television professor Kathleen McHugh, filmmaker Danis Goulet, public programmer Beandrea July, Science Fiction Against the Margins series curatorial team member and programming coordinator Nicole Ucedo. credit/ Robert Macaisa

Traditional practices and remapping histories

Sangre de Nopal/Blood of the Nopal: Tanya Aguiñiga & Porfirio Gutiérrez brings two Los Angeles-based textile artists who are indigenous to North America in direct conversation with each other’s practice. This PST Art exhibition at UCLA's Fowler Museum serves to illuminate the ecological and botanical scientific knowledge of the Zapotec peoples, which stretches back thousands of years.

The reason we have the color carmine (bright-red pigment) in our lives and textiles can be attributed to the traditional practice of cultivating and harvesting an insect called cochineal which lives on the opuntia (prickly pear), a practice these two artists have helped revive.

Image: Sangre de Nopal includes an auditorium space for events and workshops. Credit Don Cole.

The Fowler exhibition is presented in collaboration with Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara, where there is a companion exhibition titled Sangre de Nopal/Blood of the Nopal: Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Contemporary Art. It’s really an example of indigenous innovation, said Freddy Janka, board president of the Museum of Contemporary Art Santa Barbara during a press preview the day before the exhibition opened. In Zapotec there are not different words for “art” and “science,” he said.

Inside the Fowler, the artists and curators have created a space to celebrate the revival of traditional practices, invite audiences to participate in community weaving projects, and share their personal migration and labor stories.

Image: In-gallery artist talk and community weaving event for Sangre de Nopal at the Fowler Museum. Credit Hannah Yoo

“For me art is a way to help deal with the trauma and difficulty of living on the border,” said Aguiñiga, who grew up near Tijuana, Mexico and crossed the border daily for school. She said she uses craft as a way of maintaining and reviving traditions of her ancestral homeland. She creates pigments from pulverized pieces of the 30-foot-tall U.S. Mexico border wall and rust from parts of the fence that extend into the sea.

Image: Partial view of installed works by Aguiñiga. Credit Don Cole.

Gutiérrez, who has three works in exhibitions across PST Art 2024, also said he sees his work as a healing modality. He hopes the exhibitions help audiences recontextualize migration into an indigenous context and recall the fact that humans have moved across these spaces for 10,000 years without walls or lines drawn on a map to delineate nationality.

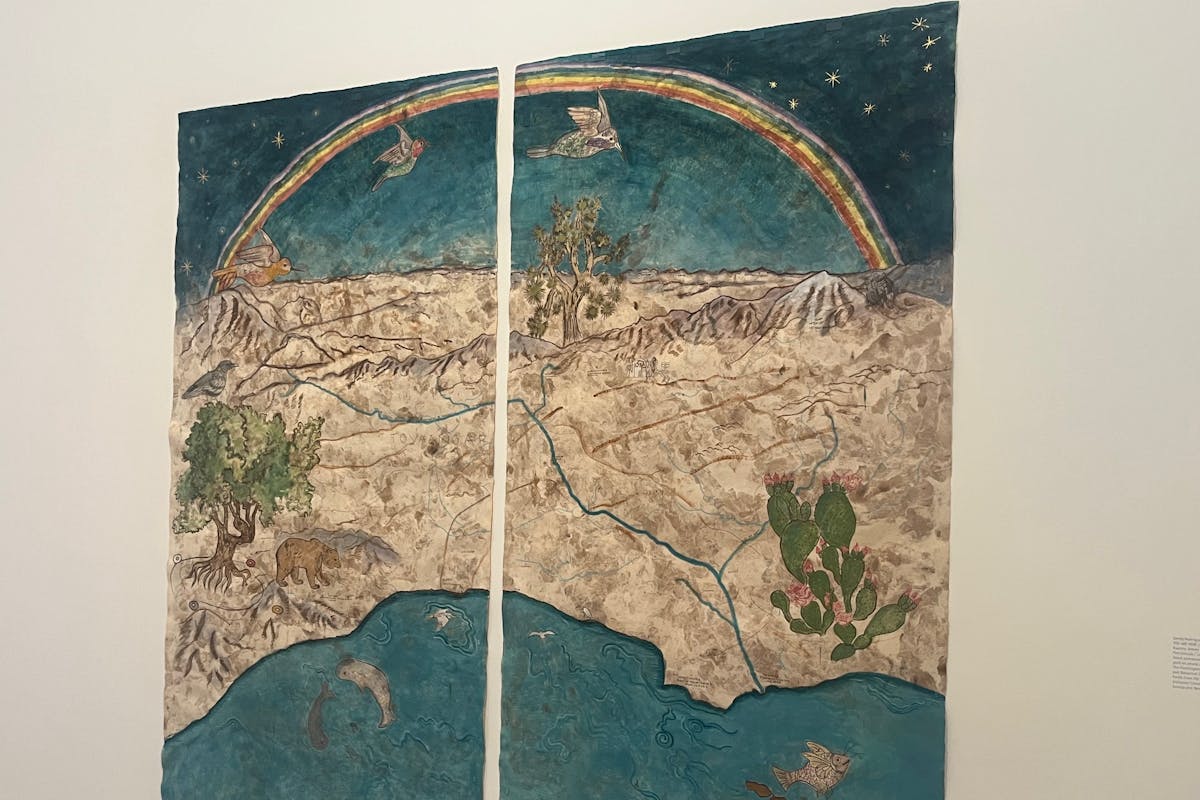

On the other side of campus at the Hammer, a thoughtfully rendered map by researcher Sandy Rodriquez from National City, Calif allows us to envision the borders and through lines of our city with an artistically expansive view.

Currently on view at the Hammer as part of Breath(e) is a unique work Rodriguez made during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the multilingual map of the greater Los Angeles area YOU ARE HERE / Tovvaangar / El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciuncula / Los Angeles (2021) draws inspirations from the region’s history.

The piece includes depictions of the trial of Toypurina, an indigenous woman who led a rebellion against the Mission San Gabriel in 1785, as well as 16th century primary source materials including the Florentine Codex, an encyclopedic ethnographic study of central Mexico. YOU ARE HERE includes images of plants and animals used by Native peoples, which represent geographic locations and serve and indicators of the cardinal directions. Place names are hand painted in English, Spanish and Tongva to reference renaming the region over time as a colonial act of aggression.

Image: Installation view at the Hammer of 'YOU ARE HERE' and 'Plant Medicine No. 2 for the Treatment of Susto' as well as a collection of natural dyes and pigments the artist uses in her practice. Credit Hammer Museum

Rodriguez studies, documents and processes native botanical specimens that have healing properties to create pigments, inks and watercolors, applying these handmade materials to amate paper made from the bark of trees in Puebla Mexico. A symbol of indigenous culture, this sacred pre-Columbian material was prohibited by the Spanish during the colonial period.

Prominent UCLA Alumni across PST Art

Several UCLA alumni are reflected across PST Art including Tongva artist Mercedes Dorame whose work appears in several exhibitions including Mapping the Infinite: Cosmologies Across Cultures at LACMA. Her sculpture titled Portal for Tovaangar (2024), helps anchor a section of the exhibition called "Tongva and Chumash Cosmologies." Drawing from her established sculptural installation practice incorporating imagined star maps, Dorame’s installation mimics constellation maps and incorporates energy fields, feathers, levitated salt crystals, and star stones. The star stones cast in concrete featured in her work reference Tongva artifacts that remain mysterious, as their purpose remains unknown.

Image: Installation view of 'Portal for Tovangaar.' Courtesy LACMA

Dorame’s contribution to the PST Art exhibition From the Ground Up: Nurturing Diversity in Hostile Environments at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena is They Dance Across the Water – Mwaar’a Hevuuchok Yakeenax, 2024. A plinth with acrylic paint on canvas holds a cast concrete bowl and star stones, cast resin, cinnamon, salt, and found stones and shell.

Images: Detail and installation view of 'They Dance Across the Water.' Photograph by Yubo Dong, of studio photography, courtesy Armory Center for the Arts.

At the Autry Museum of the American West’s PST Art exhibition, Future Imaginaries: Indigenous Art, Fashion, Technology is a series of inkjet prints titled Asphaltum Seeps – Shaanat Chuuynok’e (I-VI), from Dorame’s series Everywhere Is West. Reminiscent of a galaxy, the series evokes what Dorame describes as “portals through time and space.” Asphaltum is a multipurpose material traditionally used for both functional and decorative purposes. It is essential for constructing ti’aats (Tongva) and tomols (Chumash), seafaring boats used to cross the 24 miles to the mainland, as well as affixing decorative shell bead inlay to steatite bowls and other cultural objects.

Image: Installation view of 'Asphaltum Seeps.' Photo by MitoKino. Courtesy of the Autry Museum of the American West.

Recently named MacArthur Fellow Wendy Red Star is also part of the Autry's Future Imaginaries exhibition. Her imaginative work Stirs Up the Dust takes the traditional regalia associated with powwow, a dance celebration found throughout Indigenous Plains cultures, including her own Crow Nation, Red Star reimagines it in both feminist and futuristic terms.

Image: Detail view of 'Stirs Up the Dust.' Gift of Loren G Lipsun M.D. Autry Museum, Los Angeles. Courtesy of Wendy Red Star. Autry Museum of the American West.

“I’m really interested in introducing the art world to all the important aesthetic values of my community that are often ignored,” Red Star said. “So, I spend a lot of time looking at different cultural items and make art based on those findings.”

UCLA alumnae Sarah Rosalena (Wixárika) is an interdisciplinary artist and weaver based in Los Angeles. She teaches in the department of art at the University of California Santa Barbara. She is known for themes rooted in Indigenous cosmologies. Her approach to “computational craft” which blends analog and digital practices, appears in six different PST Art exhibitions, including a piece titled Exit Point now on view at the Hammer as part of Breath(e), made with cotton yarn and a digital training set.

Image: Detail of 'Exit Point'. Courtesy Hammer Museum

Rosalena also has pieces in the Future Imaginaries exhibition at the Autry, From the Ground Up at LACMA and the MCAB Sangre de Nopal exhibition.

Rosalena also will participate in a discussion at the Fowler on December 13 titled Indigenous Knowledge, Sustainable Future along with Gutiérrez and Lazaro Arvizu (Gabrieleno/Nahua).

Arvizu has been commissioned by the Fowler to create a piece for its upcoming exhibition Fire Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Art, titled Sand Acknowledgement, an installation that reflects traditional and ephemeral sandpainting practices that illustrate the connections between the land, humans, the sun, the stars and animals.

The art of ecology

January 12 is the opening of Fire Kinship: Southern California Native Ecology and Art at the Fowler Museum. This exhibition is a thoughtfully rendered meditation on fire as a generative force. It presents a living history that centers the expertise of Tongva, Cahuilla, Luiseño, and Kumeyaay communities past and present.

Fire Kinship seeks to counter attitudes of fear and illegality around fire, arguing for a return to Native practices in which fire is regarded as a vital aspect of land stewardship, community well-being, and tribal sovereignty. The exhibition will be on view through July 12 and present a living history that centers the expertise of Tongva, Cahuilla, Luiseño, and Kumeyaay communities past and present.

Prior to the colonization of Southern California in the 18th century, Native communities throughout the region deployed controlled fire regimes to ensure the well-being of their local ecosystems. Fire-based land management practices ranged from small burns to spur healthy growth, to larger burns that strategically eradicated invasive species and reduced fuel loads (preventing catastrophic natural fires).

Fire Kinship reintroduces fire as a generative conduit, one that connects us to our past and offers a collective path toward a sustainable future. Included in the exhibition are a collection of object-relatives that native communities used and continue to use in partnership with the land, such as baskets, ollas, rabbit sticks, and bark skirts. The creation and presentation of these objects is a result of a partnership between people, place, and fire. Other works use the color and growth patterns of the California poppy as a point of reflection, as wildfires impact the naturally occurring state flower.

A series of newly commissioned works from contemporary artists respond to these cultural objects, invoking a dialogue of critique, reflection and futurity. These include a portrait series by Weshoyot Alvitre (Tongva and Scottish) that focuses on the multilayered histories of Indigenous women, a ceramic vessel and traditional skirt made from burned cottonwood bark by Summer Paa’ila Herrera (Payómkawichum), and The Heart is Fire—a multimedia work with video, birdsong audio and natural materials by Gerald Clarke Jr. (Cahuilla Band of Indians).

Image: In-progress view of newly commissioned work. Credit: Todd Westphal

With the support of nearly $20 million in grants from Getty, dozens of cultural, scientific, and community organizations have been presenting more than 70 exhibitions and an extraordinary spectrum of public programs. UCLA holds the largest footprint in PST Art 2024, with $2 million in support for projects from UCLA’s Film & Television Archive, all the public arts units of the School of the Arts and Architecture—the Hammer Museum at UCLA, the Fowler Museum at UCLA, UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance—as well as two research labs in the school, The Conditional Studio and the ArtSci Center.

Story by Jessica Wolf

Posted 11.26.24